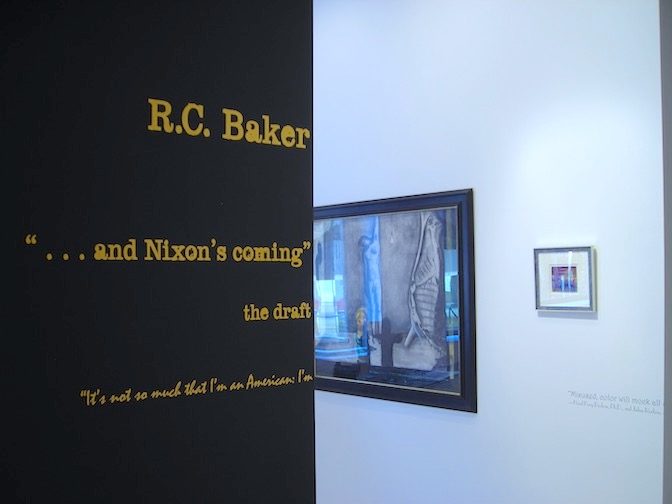

The Brooklyn Rail reviews RC Baker’s solo exhibition, “…and Nixon’s coming” the draft

by Emily Warner

Zone: Contemporary Art, April 2-May 30, 2009

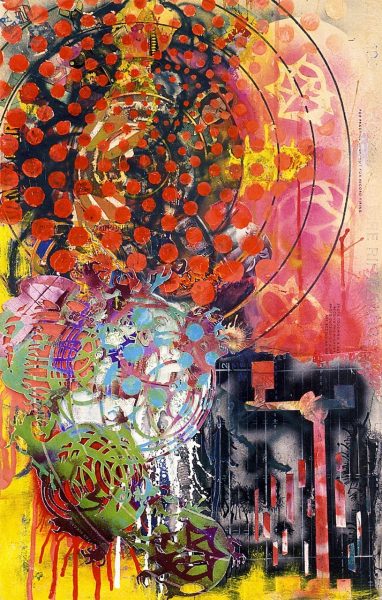

Kirby Holland, the fictional protagonist of R. C. Baker’s ongoing novel-cum-exhibition, explains his art-making process this way: “I put…these collages…together as grounds, the surface you paint on,” before laying the abstract designs on top: “I need some grit, something to hang my compositions on.” That description is a fitting one for Baker’s project as a whole, a collage-like, multimedia narrative that uses the structures of history as the grit for its fictional tale. The edges of the story emerge like pieces in a puzzle: chapter headings line the gallery walls (“Part i: The Fractured Century”), and scribbled notes and studies sketch out forms fully realized in paintings across the room. As a writer, artist, graphic designer, and art critic, R. C. Baker is a polymath, and his current project is a testament to the richness of overlapping artistic modes.

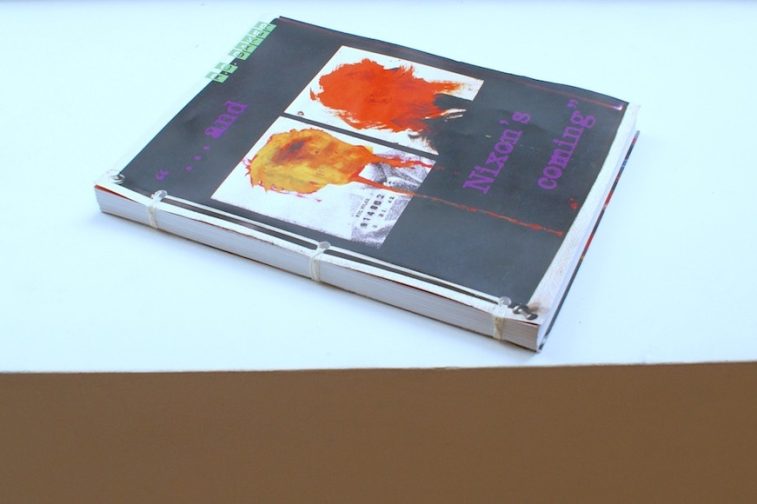

In its present installation, “…and Nixon’s coming” lives in two places, Baker’s in-progress novel draft (available for perusal and purchase at the gallery) and the exhibition. Neither is definitive. In fact, what makes the project so compelling is the detective work the viewer must do to fill in the story’s gaps, linking motifs from work to work, and from text to image. At the center of the narrative is Kirby Holland, to whom all the work in the show (made by Baker over the last few decades) is attributed. Written in the novel in a jaunty third-person, Holland seems more stock figure than fleshed-out character. It’s in his putative drawings, studies, and paintings—intimations of an inner personality and a set of working artistic concerns—that we really catch a believable glimpse of him.

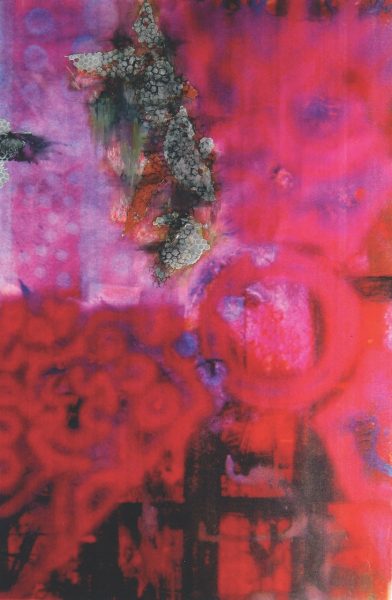

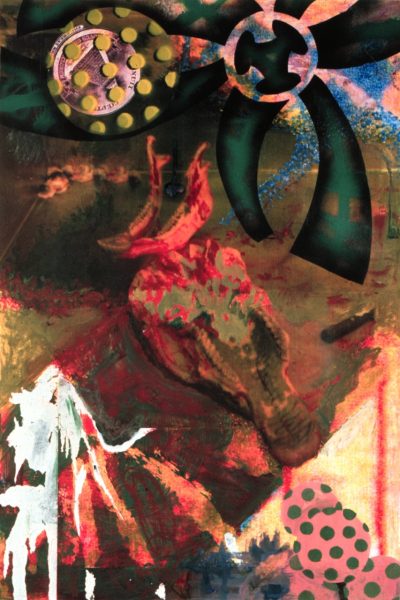

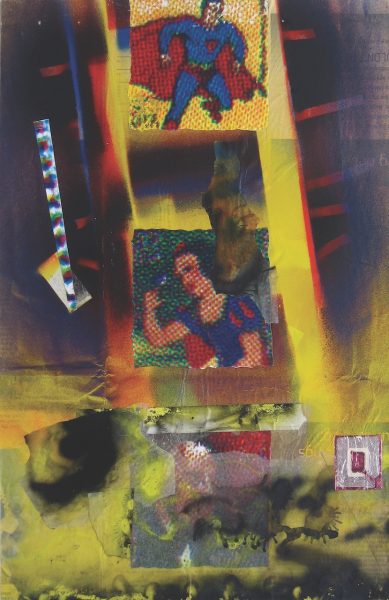

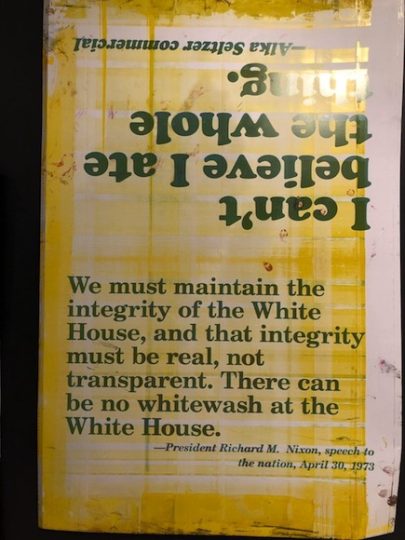

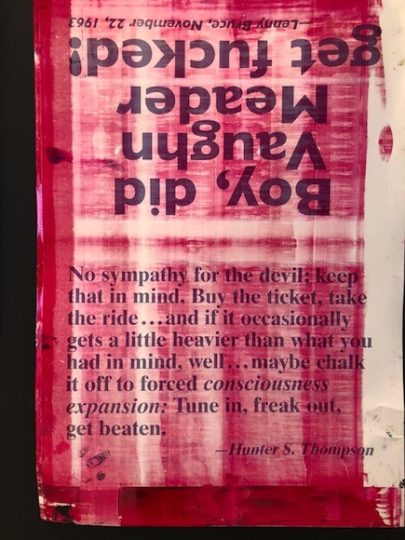

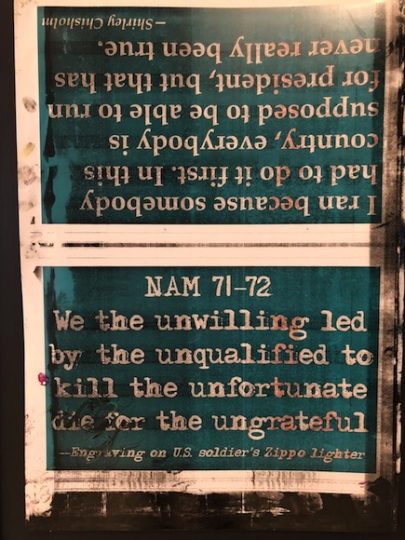

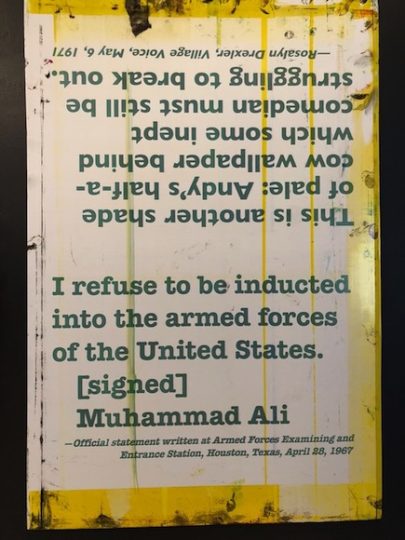

That glimpse plunges us into a cultural and art historical tangle: in Holland’s oeuvre are references to Eakins, Hopper, comic books, Abstract Expressionism, war, and nuclear disaster. These references are constantly edited into new combinations and overlaps. Nothing is ever final in Baker’s project, and a sense of textural, pulpy accumulation—the accretion of drafts, collage layers, galley pages, reworked storyboards—runs throughout. A few pieces are executed directly on printing-press waste; in another series, flung drips of paint are outlined with careful, colored contours, lending high painterly abstraction the printed oomph of a comic book splat. It’s the visual slag of American history, and the manipulations and rewrites to which we subject it, that forms the real subject of the exhibition.

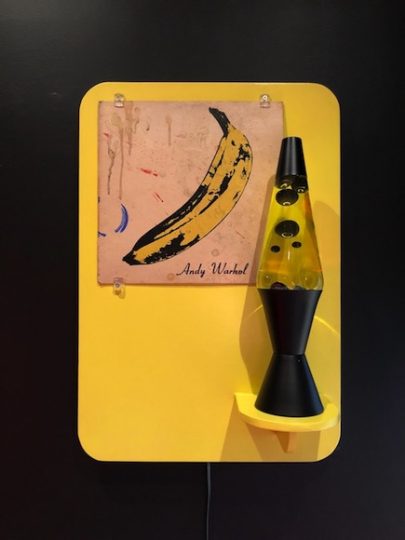

This reworking is not just an aesthetic project; the pithy (if dizzyingly self-referential) “After Krivov, Rockefellers, and Warhol” takes us into more pointedly political terrain. Caked gouache, splotched onto a woolly black xerox of Andy Warhol’s infamous “13 Most Wanted Men,” blots out the face of each mug shot. The work alludes to the whitewashing of the original 1964 Warhol mural by Nelson Rockefeller, and also to the actions of N. A. Krivov , a fictional Soviet filmmaker we meet in the novel as he peruses Stalin-doctored photographs with their unwanted members airbrushed out of the scene. Reproduction and erasure, Baker suggests, are dangerous if creative prospects, and we find them in the paranoid machinations of Soviet Russia as often as in the bourgeois mores of capitalist America.

Of course, the question remains: how effective is Baker’s occasionally bizarre project? For it to work, you need to be curious enough to follow up on its disparate threads. Many viewers may stop here, uninterested in penetrating its rather insular depths. Other authors have used a non-fiction model as the structure for their fictive worlds and characters (John Dos Passos’ USA trilogy and William Boyd’s Nat Tateboth come to mind), and yet Baker’s project stands somehow outside of this vein. His characters lack the practiced interior nuance of properly literary personages and the writing, while always vivid, can be heavy-handed. Indeed, thinking of “…and Nixon’s coming” as a literary project may be the wrong way to go. It’s more a purely visual narrative: the paintings, the sketches, the space of the show act as vignettes, imagistic moments taken from a shifting storyline.

The rewriting we see in the visual works is directed in toward the author, too: Baker has sampled from pieces completed long ago in other contexts, assigning them new authorship and meanings. Krivov, lying in the snow at the feet of Soviet interrogators, performs his own kind of interior rewrite, a cinematic fade-out of the scene around him: “Ah, look how the sun turns that scrub tree into black tendrils…You could fade into a witch’s claw or the Devil’s hand from that,” he thinks. “But that’s stupid and obvious.” There are moments in Baker’s project that feel obvious, too. But it’s nevertheless a vivid evocation of postwar America, and a compelling meditation on the politics of reproduction and appropriation. Eminently fluid and rewritable, Baker’s draft implies that making art is always a form of manipulation, and at times a dangerous one. His project speaks eloquently to the attempt to forge something real—to pick out a storyline—from the mess that is lived experience.

Source: https://brooklynrail.org/2009/06/artseen/rc-baker-and-nixons-coming-8260-the-draft

Related:

The Brooklyn Rail reviews RC Baker’s solo exhibition, “…and Nixon’s coming” the draft

PICASSO, WELCOME TO AMERICA

Madison Ave New York

Picasso, Welcome to America

June 15 – September 27, 2023

R.C. Baker

Brandon Ballengée

Romare Bearden

Deborah Buck

Shijia Chen

Billy Copley

Eileen Foti

Björn Meyer-Ebrecht

Jaye Moon

Pablo Picasso

André Raffray

Janet Taylor Pickett

Zhang Hongtu

Every artist since the early 20th century has been influenced by Pablo Picasso. The protean painter/ sculptor/ printmaker/ ceramicist helped define what “modern” art once was – and is still becoming. In 1939, MoMA’s staff was gathering 300 works by the world’s “most famous living artist” (according to the museum’s press release) for Picasso: Forty Years of His Art. A centerpiece of the exhibit was Guernica, his grisaille mural decrying the destruction of the small Basque town by Nazi bombers, in 1937.

Along with Michelangelo and Rembrandt, the name Picasso (1881-1973) has become a synonym – a cliché, even – for “artist.” But none of the artists in Picasso, Welcome to America see the Spanish-born titan as an old hat. Instead, these ten Americans find in the European trailblazer constant inspiration and ongoing challenge. Zhang Hongtu imagines Chairman Mao exposed by glaring illumination similar to the all-seeing lantern in Guernica. Jaye Moon also reimagines Picasso’s anti-war masterpiece, in When Bob Dylan Meets Picasso, Guernica – using Lego bricks in Braille rather than paint.

The bodies and masks in another Picasso touchstone, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), come under scrutiny from Eileen Foti and André Raffray through substitution and homage. Billy Copley finds masks in unlikely surroundings, while Janet Taylor Pickett moves effigies aside to place her powerful female figure at center stage. Deborah Buck turns Picasso’s infamously harsh male gaze around, painting surreal figures that might be asking, “Who’s crying now?” In Weary of Treading the Earth, from 1945, Romare Bearden, working in watercolor and ink rather than his later signature collage, energizes cubist space with a circus-like palette. R.C. Baker riffs beyond Picasso’s Blue and Rose periods through primary-colored aluminum printing plates. Björn Meyer-Ebrecht’s dynamic wood and enamel sculpture strips the figure to cubist angles and voids, while Brandon Ballengée searches for animals that, like Picasso’s minotaurs, are no longer with us. Original works by Pablo Picasso will also be on view, commemorating the 50th anniversary of his death.

All of the artists in this exhibition have been influenced by Picasso’s experiments with form and perspective – his breaking of traditional and academic rules. Some of the work here also comments on his darker side, while other pieces engage with the social and political aspects of Picasso’s art. Ultimately, these ten contemporary artists in Picasso, Welcome to America appreciate the formal and aesthetic complexity of a constant innovator. This great artist was effectively barred from ever visiting the United States because he was a member of the French Communist Party. But the joke was on the Feds – Picasso has been in America all along.

VIDEOS

RELATED:

The Brooklyn Rail reviews RC Baker’s solo exhibition, “…and Nixon’s coming” the draft

Jaye Moon is included in the New York Foundation for the Arts exhibition

Janet Taylor Pickett is included in Century: 100 Years of Black Art at MAM

BROOKLYN RAIL reviews Deborah Buck: INTO THE WILD, To Crash Is Divine

Categories: exhibitions

Tags: André Raffray Billy Copley Björn Meyer-Ebrecht Brandon Bellengee Deborah Buck Eileen Foti Janet Taylor Pickett Jaye Moon Kathy Grove Pablo Picasso RC Baker Romare Bearden Zhang Hongtu

PITCHES & SCRIPTS

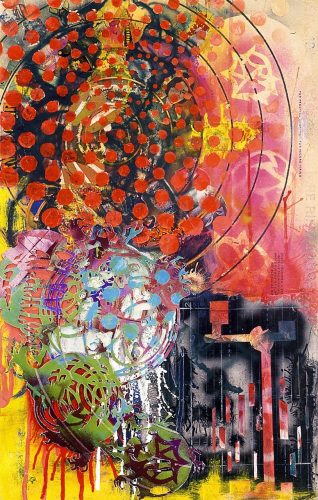

Pocket MonstersTM Strobe, 2000

Gouache on color laser copy and collage

16 3/4 x 10 7/8 in.

Weed whacker, 2002

Inkjet on paper

11 x 9 in.

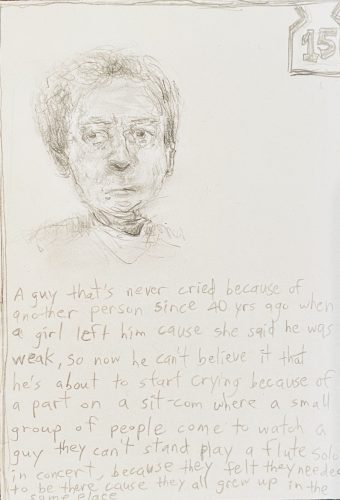

#15 (Card Series 2), 2006

Pencil on paper

4.25 x 3 in.

Untitled (Fountain), 2019

Ink and tape on paper

88 x 88 1/2 in.

Dresses Akimbo (Blue Sky), 2015

Acrylic, vintage photos, inkjet print, collages on paper

8 x 7 in.

Long Live Mao, solo, 1987

Acrylic on found Quaker Oats cereal box

9.75 x 5.25 in.

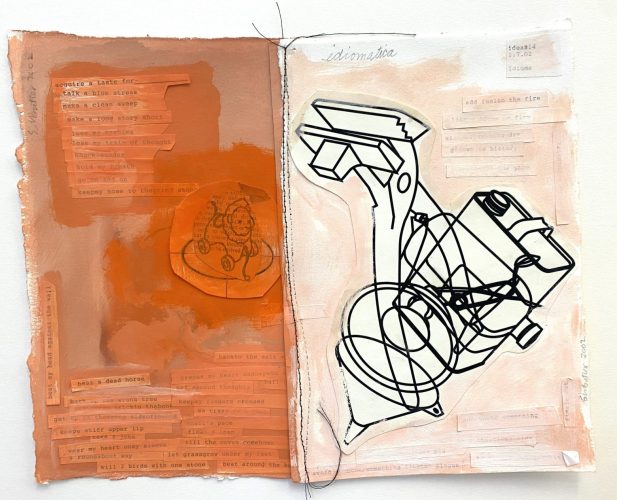

Idiomatica, 2002

Acrylic, sewing, inkjet print, collages on paper

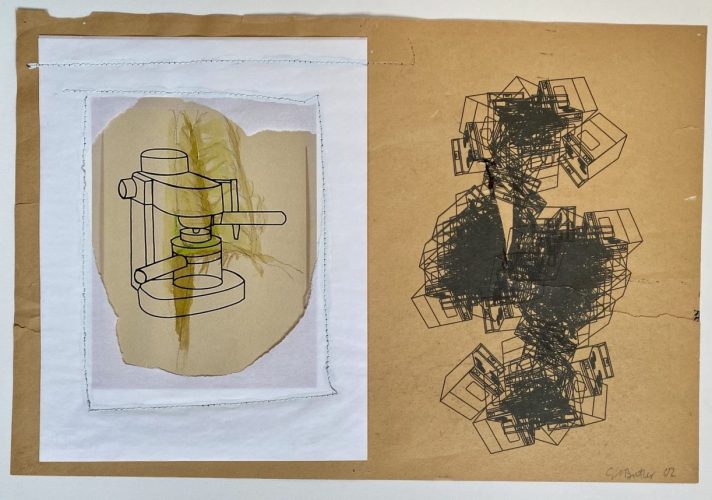

11 x 14 in.

Louise Bourgeois, 2002

Acrylic, pen, pencil, inkjet print, sewing, collages on paper

11 x 17 in.

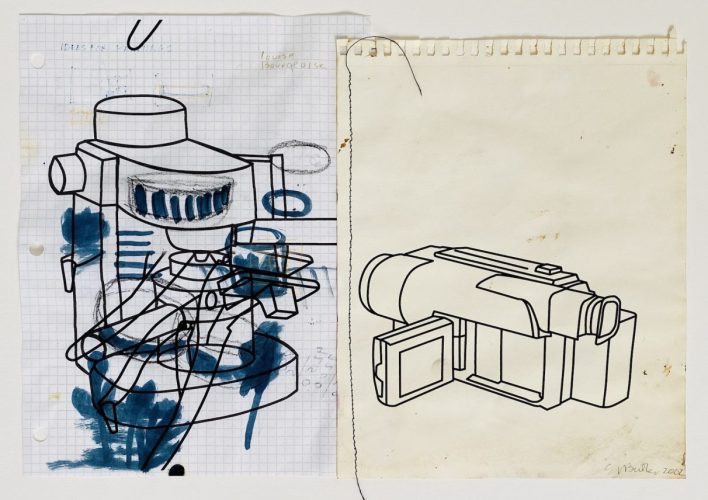

Caffeinated, 2002

Inkjet print, sewing, collages on paper

12 x 18 in.

PITCHES & SCRIPTS

January 20 – March 11, 2023

Jennifer Baahng Gallery is pleased to present PITCHES & SCRIPTS, a group exhibition of works on paper. On view are ink and graphite drawings, collages, inkjet prints and sewed surfaces produced from the 1980’s through 2020. In pooling together six artists, the exhibition pitches a fermentation of ideas, technologies, and political stances that connote rupture and disintegration, while scripting growth, movement and new life. PITCHES & SCRIPTS runs from January 20 through March 11, 2023, with its opening reception on Friday, January 20, 6 – 8 PM.

The spectral presence of history suffuses the work of Janet Taylor Pickett and Zhang Hongtu. Blackness is a “declarative statement” for Janet Taylor Pickett (b. 1948), whose works, as ongoing visual poems, probe personal and collective memory. Dresses Akimbo, on view, elaborates upon the symbolism of that gesture: a stance of power, bewilderment, and love. A forerunner of Chinese Political Pop Art whose work engages a multilayered discourse, Zhang Hongtu (b. 1943) asserts themes of dislocation, national identity, propaganda, and politics in the Long Live Mao series, which is equal parts whimsical and profound.

Idiomerica by Sharon Butler (b. 1959) was catalyzed by the artist’s move from New York City to the suburbs. The works investigate the visual grammar of capitalist suburban Americana through video animations, text projects, digital drawings, and the resulting tendencies of reductive art. Conversely, moving from the Midwest to New York City, Jeff Gabel (b. 1968) developed Short Fiction Sketches in scribbly and smudge tone drawings. The works externalize the imagination of a solitary artist inducted into a sea of uncanny urban experiences.

The Terminal Century by R.C. Baker (b. 1960) seethes with existential angst, as painted and collaged elements tremor with disruption and discordance, while also pointing to the beauty nestled in such moments of ostensive entropy. Similarly responding to a post-War world order, Bjorn Meyer-Ebrecht (b. 1972), makes ink drawings at a monumental scale, creating a pictorial architecture in ink that displays luminous materiality. In their rich, textured surfaces, the works included push the pictorial plane from drawing into painting.

PITCHES & SCRIPTS assembles the memories of the artists at a formative historical moment, and inquires how art shapes history by responding to cultural shifts or by instigating them itself. As we are flung—‘pitched’—into the future, the exhibition looks to this collection of work for a loose, dynamic script for how to narrativize ourselves in the present. PITCHES & SCRIPTS renders a ‘soft landing’ for our launch into the new year.

Related:

The Brooklyn Rail reviews RC Baker’s solo exhibition, “…and Nixon’s coming” the draft

Adam Simon reviews Sharon Butler’s “Next Moves” in the October 2022 issue of The Brooklyn Rail

Janet Taylor Pickett is included in Century: 100 Years of Black Art at MAM

Categories: exhibitions

Tags: Björn Meyer-Ebrecht Janet Taylor Pickett Jeff Gabel RC Baker Sharon Butler Zhang Hongtu

RC Baker “…and Nixon’s coming” | the draft Artist Talk and Reading

Artist’s Talk and Reading, Saturday 1pm, April 18, 2009

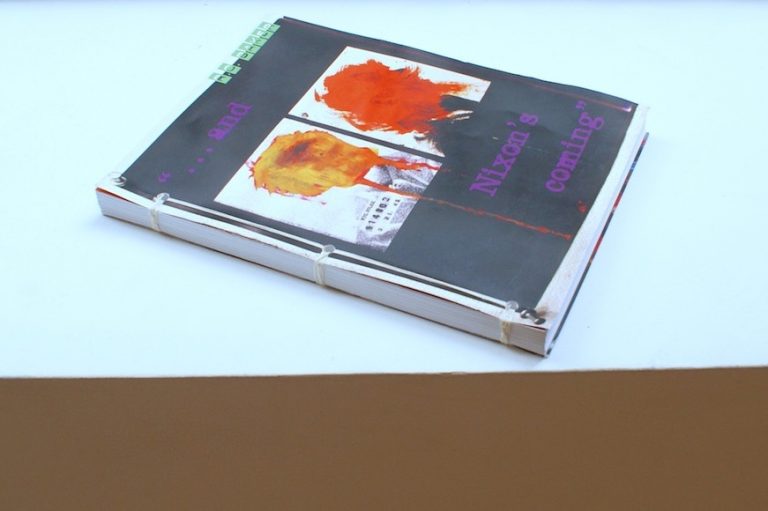

"...and Nixon's coming" | the draft

Baker's talk and reading, April 18, 2009

Baker's talk and reading, April 18, 2009

Accompanying the exhibition “…and Nixon’s coming” | the draft, ZONE: CONTEMPORARY ARTS presented Artist’s Talk and Reading. Mr. Baker read from “…and the Nixon’s coming” | the draft and discussed the works in the exhibition as well as relationship between criticism and fiction.

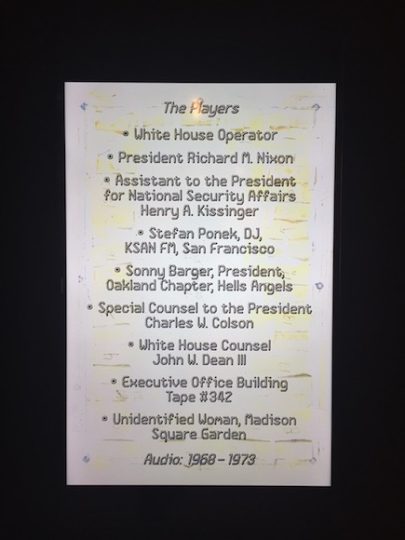

“ . . . and Nixon’s coming” combines art, fiction, and design to create a multifaceted narrative that arcs from the Moscow show trials of 1937 to President Nixon’s resignation, in 1974. Divided into four sections, the work views the turbulent artistic and social ferment of the mid-20th century through the experiences of the story’s main character, Kirby Holland, and through his artwork, including academic drawings, comic-book illustrations, and amalgams of Abstract Expressionism, Pop, and graphics. Whether figurative or abstract, none of the art functions as illustration; rather, the images create a parallel track to the text. Holland progresses from earnest art student to member of an army unit charged with repatriating Nazi loot to comic-book illustrator caught up in McCarthy-era witch hunts to determined and eclectic painter at a time—the 1970s—when painting was viewed by many as irrelevant, if not dead.

Related:

The Brooklyn Rail reviews RC Baker’s solo exhibition, “…and Nixon’s coming” the draft

Artist Talk with RC Baker ranging from Old masters to comic books, political echo chambers and the joys of dissolving 60s protest posters into psychedelic abstractions

In conjunction with the exhibition Noise For Signal, R.C. Baker presented a talk ranging from Old Master paintings to comic books, political echo chambers, and the joys of dissolving 60s protest posters into psychedelic abstractions.

Saturday June 16th, 2018

Youtube video of the talk

Related:

The Brooklyn Rail reviews RC Baker’s solo exhibition, “…and Nixon’s coming” the draft

R.C. BAKER: “…and Nixon’s coming” | the draft

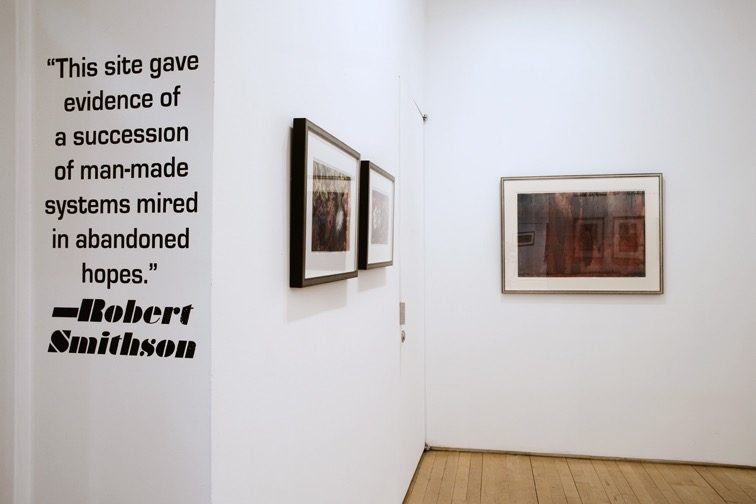

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

"...and Nixon's coming" | the draft

Baker's talk and reading, April 18, 2009

Baker's talk and reading, April 18, 2009

ZONE: CONTEMPORARY ART is pleased to present “ . . . and Nixon’s coming” | the draft, R.C. Baker’s first solo exhibition with the gallery.

“. . . and Nixon’s coming” combines art, fiction, and design to create a multifaceted narrative that arcs from the Moscow show trials of 1937 to President Nixon’s resignation, in 1974. Divided into four sections, the work views the turbulent artistic and social ferment of the mid-20th century through the experiences of the story’s main character, Kirby Holland, and through his artwork, including academic drawings and studies after the old masters, comic-book illustrations, and amalgams of Abstract Expressionism, Pop, and graphics. Whether figurative or abstract, none of the art functions as illustration; rather, the images create a parallel track to the text. Kirby progresses from earnest art student to member of an army unit charged with repatriating Nazi loot to comic-book illustrator caught up in McCarthy-era witch hunts to determined and eclectic painter at a time—the 1970s—when painting was viewed by many as irrelevant, if not completely dead.

The book “ . . . and Nixon’s coming” is a work in progress, created with varying fonts, layouts, and graphics—a literary/historical/graphic-novel/art-catalogue hybrid. The images for Part i, “The Fractured Century,” set in the years 1937–47, include still lifes, figure drawings, and early abstractions. Part ii (“Smashin’ Pumpkins,” 1952–55) features black-and-white action paintings, comic-book pages, and large-scale collisions of the two. Layered abstractions and reconceptualized Pop portraits appear in Part iii, “Incoming” (1964–68); dense collages and painterly graphics characterize Part iv, “What? My Lai?” (1972–74). All of the paintings, drawings, and prints were actually created between 1979 and 2009, with additional work planned as the book progresses.

On Saturday, April 18, at 1 pm, Mr. Baker will read from “ … and Nixon’s coming” and discuss the work in the exhibition as well as the relationship between criticism and fiction.

R.C. Baker’s articles and essays have appeared in TheVillage Voice, Performing Arts Journal,The New York Times,and other publications, and his paintings, drawings, and artist’s books have been exhibited at numerous venues in New York City, including the Drawing Center, White Columns, and the Center for Book Arts. Mr. Baker is the recipient of a New York Foundation for the Arts Painting Fellowship and has taken part in numerous panels discussing subjects ranging from “The Future of the Graphic Novel” to last year’s Whitney Biennial. He most recently appeared as a talking head for the Ovation channel’s documentary Jeff Koons: Beyond Heaven.

A solo exhibition by R.C. Baker

April 2 – May 30, 2009

Opening reception

6-8PM, Thursday, April 2, 2009

Artist’s Talk

1PM, Saturday April 18, 2009

Related:

The Brooklyn Rail reviews RC Baker’s solo exhibition, “…and Nixon’s coming” the draft

Categories: exhibitions

Tags: RC Baker

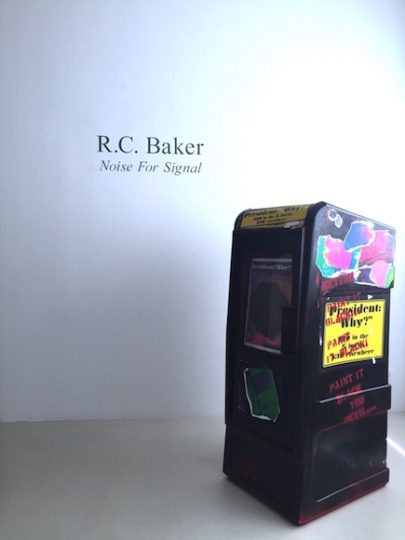

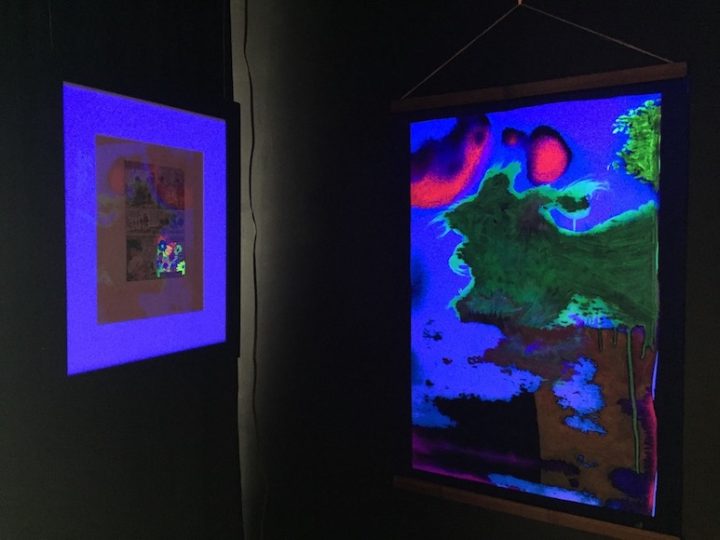

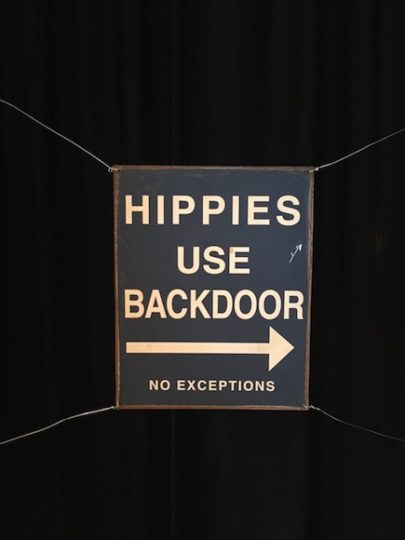

R.C. BAKER: Noise For Signal

Degeneration Mural – Noise For Signal

Installation view

Installation view

Those Newspaper Distribution Blues

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

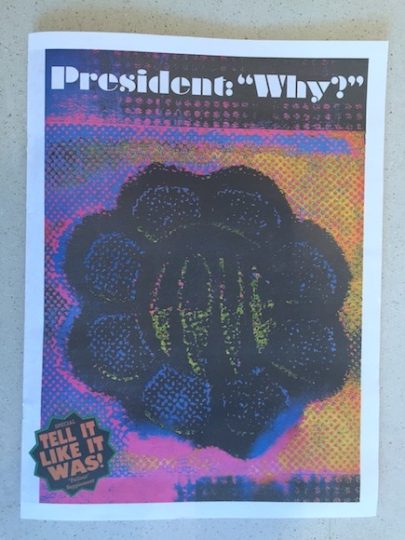

President: "Why?"

Video animation, installation view

Installation view

Death of Print

Installation view

Tell It Like It Was! series

Installation view

Tell It Like It Was! series

Installation view

Tell It Like It Was! series

Installation view

Tell It Like It Was! series

Installation view

Holy of the Holies

Installation view

President: "Why" Tabloid

President: "Why?"

Video animation, installation view

Degeneration Mural – Noise For Signal

Installation view

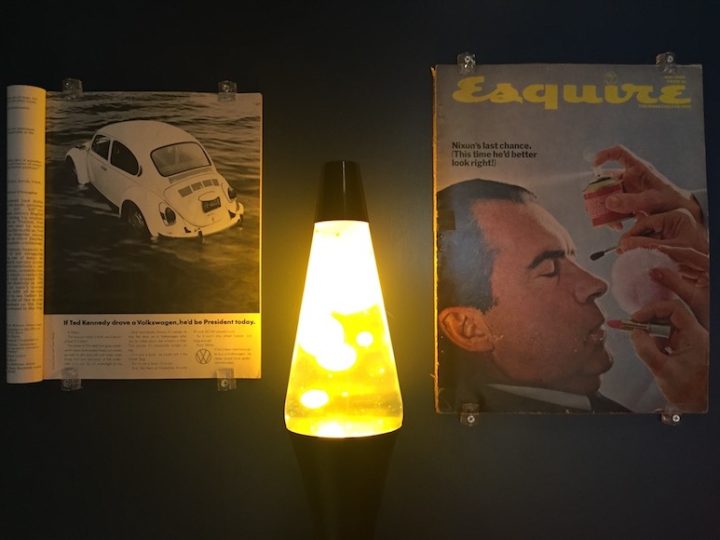

Progressives everywhere were shattered: How was it possible that a demagogic, thin-skinned, petty — and c’mon, the man is a congenital liar! — how was it possible that this charlatan had been elected president of the United States of America?

Welcome to 1968. Richard M. Nixon won the White House by less than 1 percent of the popular vote. During a 1971 discussion with National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger, Nixon griped that the members of his cabinet, including a young Donald Rumsfeld, “don’t know what the hell they’re talking about!” This observation, along with other salty insights from Oval Office recordings of our most Shakespearean president, provides the dialogue for R.C. Baker’s 9-and-half minute animation, “President: ‘Why?’ ”

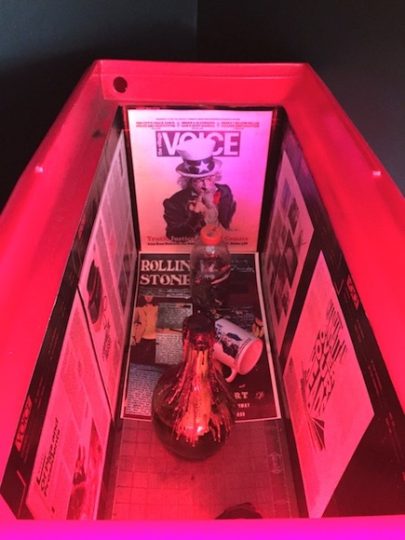

The animation was created from approximately 3,600 “degeneration prints,” a selection of which will be on view in a mural-scale installation, along with posters and assemblages. The source materials for the degeneration prints are thumbnail reproductions of head-shop posters advertised in early-1970s comic books, distorted by cheap printing techniques. Baker’s process, which he terms “painting by other means,” pushes these flaws over the border between recognizable imagery and abstraction, revealing the towering ideals of the ’60s as battered and degraded, yet still beautiful.

R.C. Baker is an artist and writer who lives and works in New York City. He is a New York Foundation for the Arts Painting Fellow whose work has been exhibited at Baahng Gallery, Zone: Contemporary Art, the Drawing Center, White Columns, the Center for Book Arts, and other venues in New York City, as well as internationally. Baker is a senior editor at the Village Voice and a visiting artist at NYU Steinhardt School of Painting. In 2016 he was awarded a Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant for Short-Form Writing.

A solo exhibition by R.C. Baker

May 24 – June 30, 2018

Opening reception

6-8PM, Thursday, May 24, 2018

Artist’s Talk

6PM, June 16, 2018

SPOTLIGHT

In conjunction with the exhibition Noise For Signal, R.C. Baker presented a talk ranging from Old Master paintings to comic books, political echo chambers, and the joys of dissolving 60s protest posters into psychedelic abstractions.

Saturday June 16th, 2018

Related:

The Brooklyn Rail reviews RC Baker’s solo exhibition, “…and Nixon’s coming” the draft

Categories: exhibitions

Tags: RC Baker