“Jackie Matisse” participated Virtuality Conference in Turin, Italy

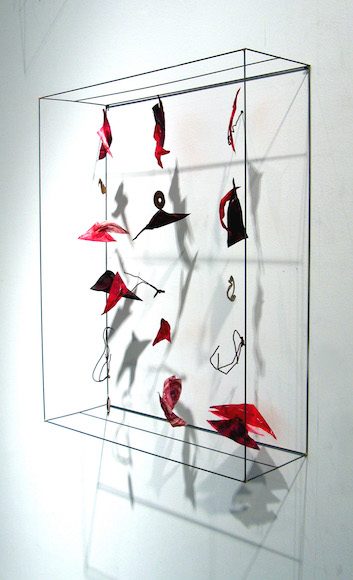

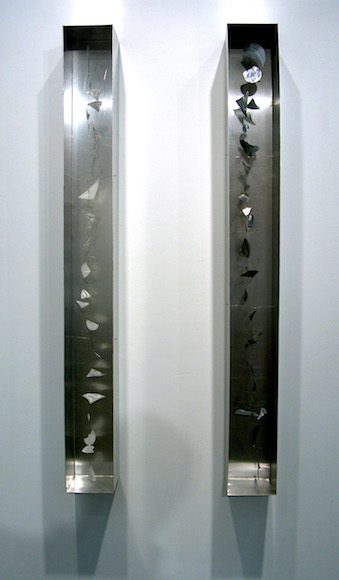

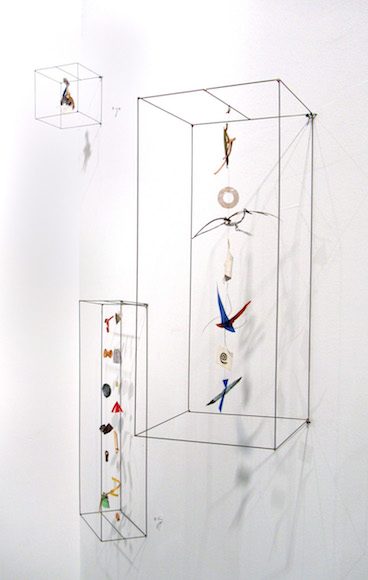

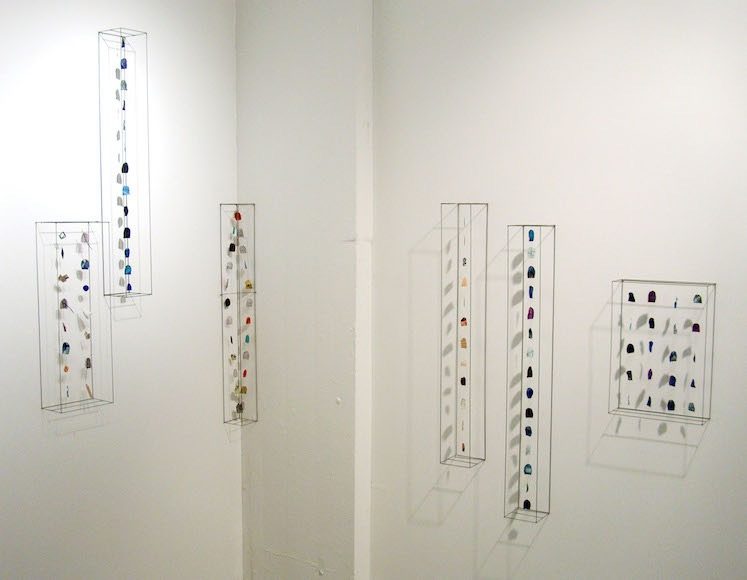

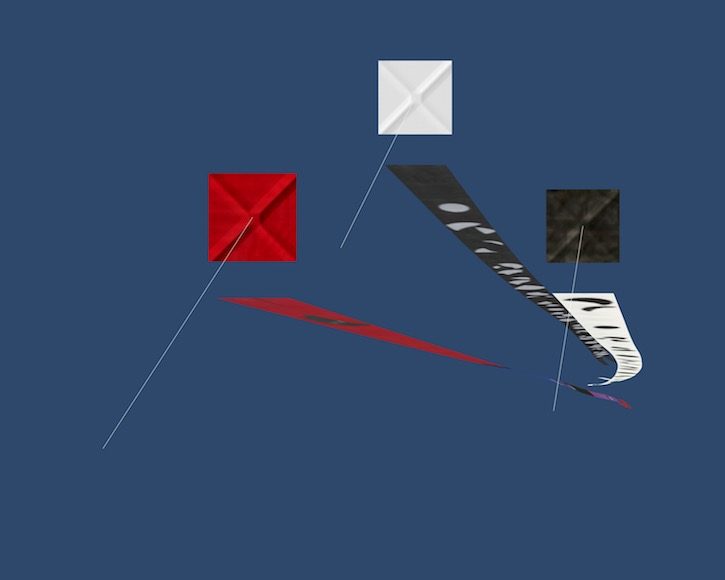

Kites Flying In and Out of Space

at Virtuality Conference in Turin, Italy

Kites Flying In and Out of Space

at Virtuality Conference in Turin, Italy

Kites Flying In and Out of Space

at Virtuality Conference in Turin, Italy

Kites Flying In and Out of Space

at Virtuality Conference in Turin, Italy

Kites Flying In and Out of Space

at Virtuality Conference in Turin, Italy

Virtuality is a premiere international event on Computer Graphics, Interactive Techniques, Digital Cinema, 3D Animation, Gaming and VFX. Every year, Virtuality proposes the most up-to-date discussion about cutting-edge applications of VR and Interactive Techniques in various fields. Particular attention is paid to industrial applications and to the multifaceted universe of cinema, including presentations by world-class experts of animation and visual effects.

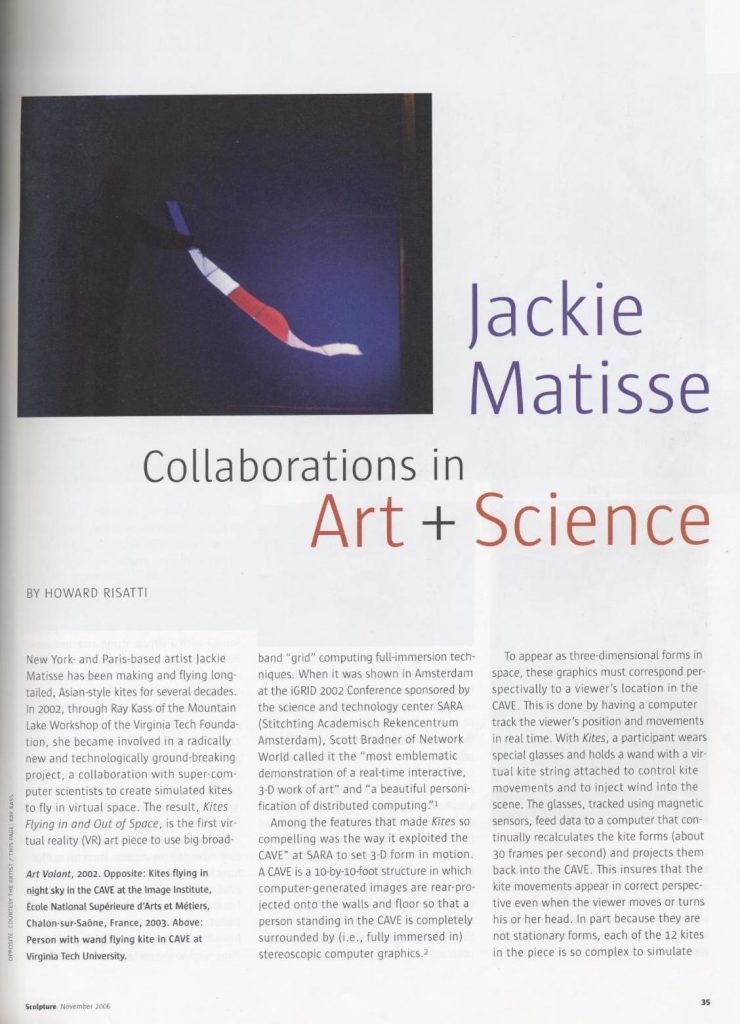

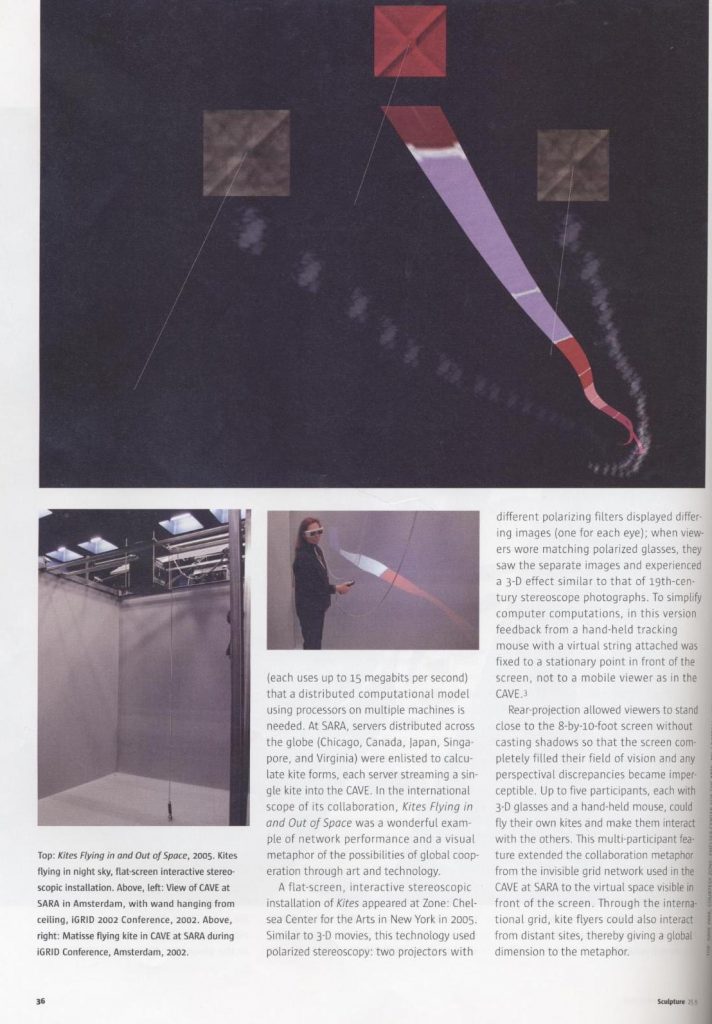

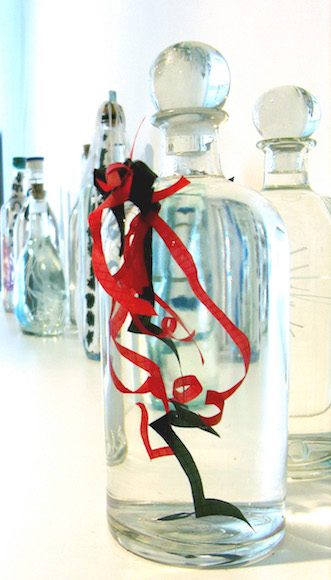

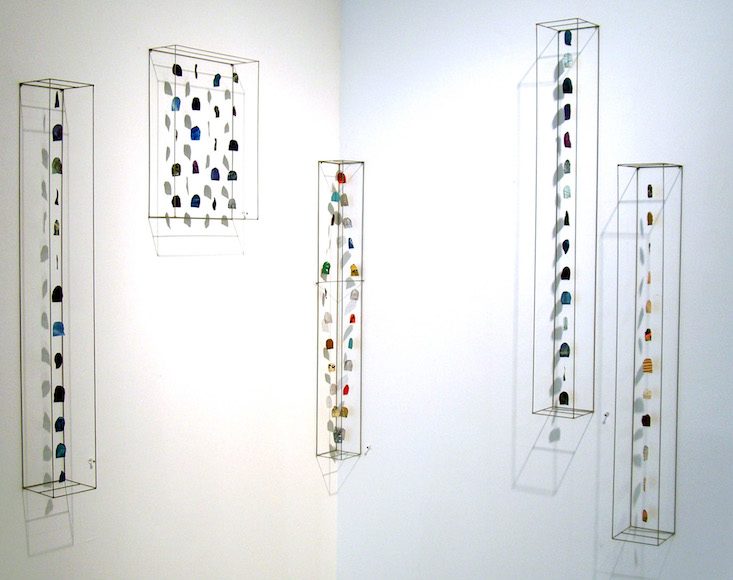

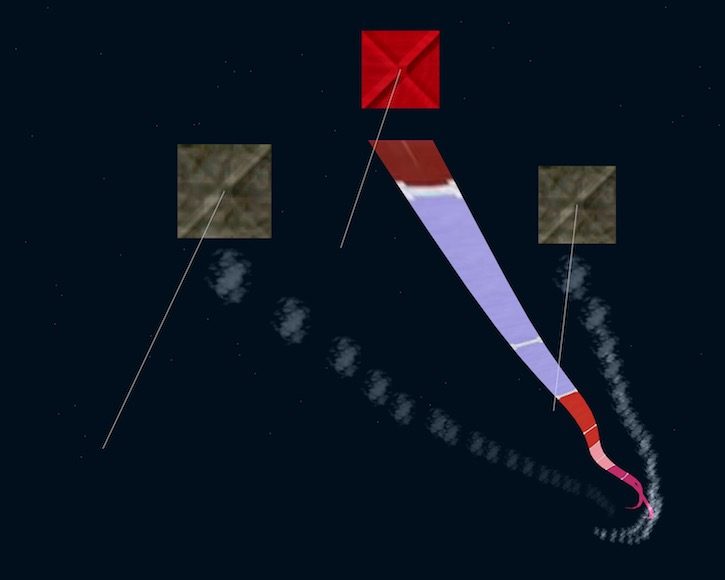

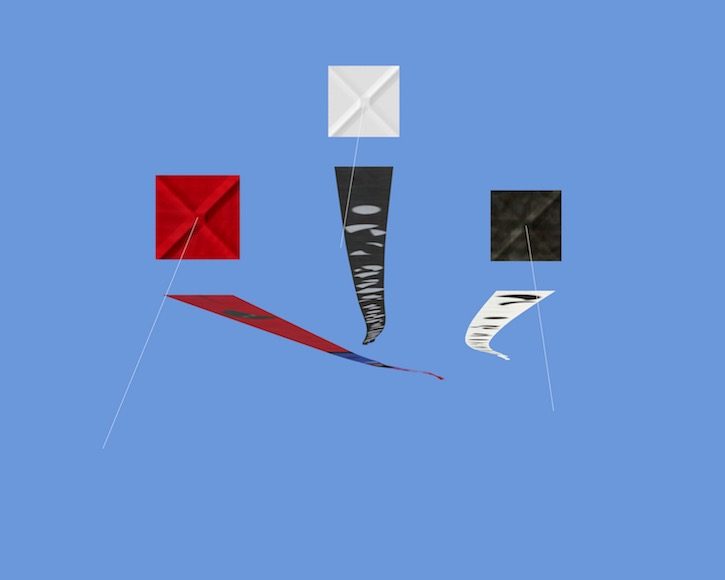

“Kites Flying in and Out of Space is the first virtual reality (VR) art piece to use big broadband grid computing full-immersion techniques. For the kites to appear as three-dimensional forms in space, the computer-generated images must correspond perspectivally to a viewer’s location in the CAVE. A CAVE is a 10-by-10-foot structure in which computer-generated images are rear-projected onto the walls and floor so that a person standing in the CAVE is completely surrounded by stereoscopic computer graphics.

With Kites, a participant wears special glasses and holds a wand to control kite movements and to inject wind into the scene. The glasses, tracked using magnetic sensors, feed data to a computer that continually recalculates the kite forms and projects them back into the cave.

Scott Bradner of Network World called Kites Flying in and Out of Space the most emblematic demonstration of a real-time interactive, 3-D work of art and a beautiful personfication of distributed computing.”

(Taken from Howard Ristatti’s article “Jackie Matisse, Collaborations in Art and Science.” Sculpture Magazine. November, 2006.)

Jackie Matisse

Kites Flying In and Out of Space

Virtuality Conference

Turin, Italy

November 3 – 6, 2005

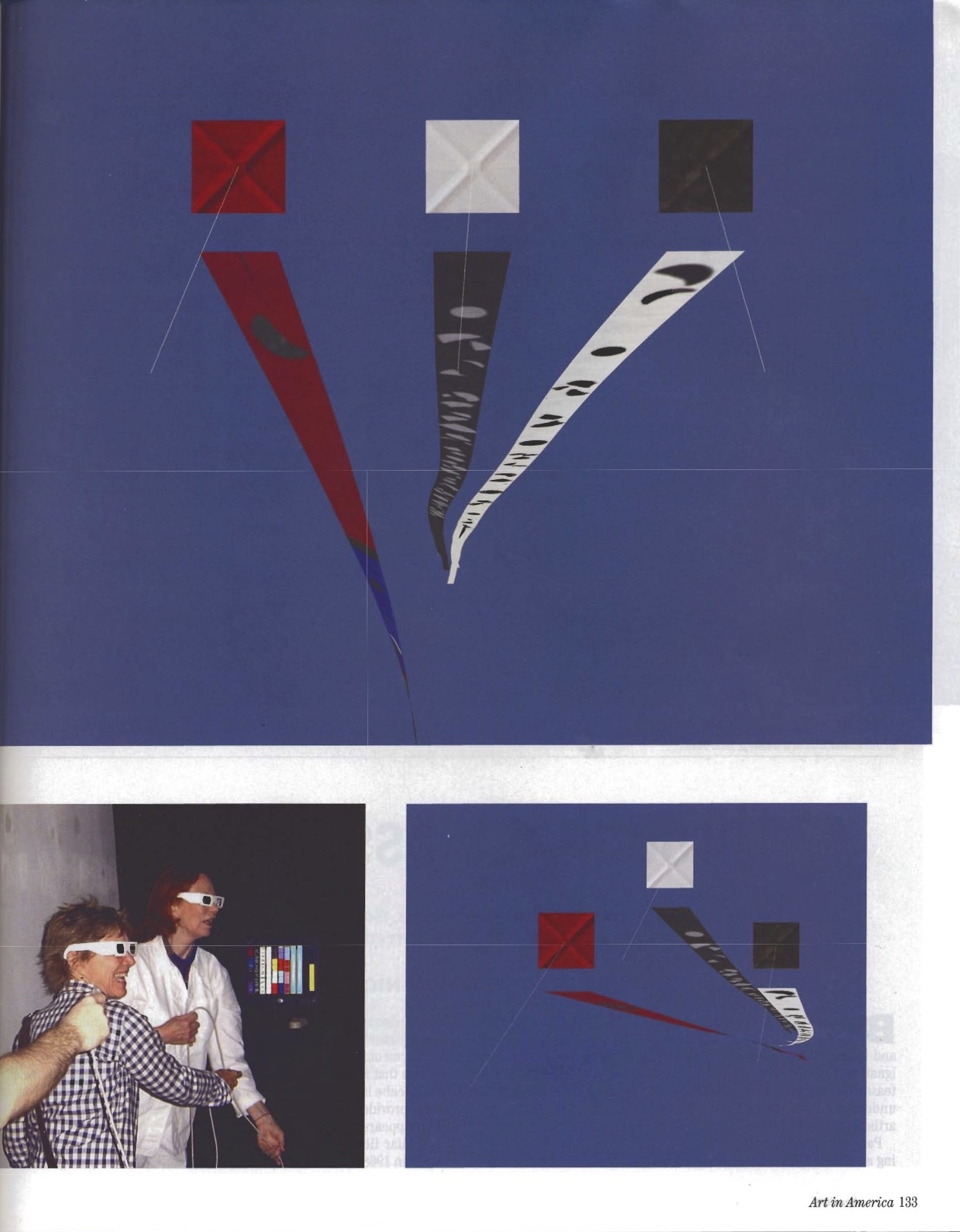

“Art Flying In and Out of Space” is a virtual reality simulation of Jackie Matisse’s real-world physical kites, although we may be calling it an ‘interactive stereoscopic installation’ rather than VR in this case. The installation is what’s called a projection-based VR system, as apposed to the perhaps more familiar head-mounted display, where users wear a helmet with computer displays attached. Projection-based VR started with the CAVE system developed at the University of Illinois’ Electronic Visualization Laboratory. One of the key elements of VR is to immerse the viewer in the virtual world (note that the meaning of ‘immersion’ is very loose and often up for debate). Head-mounted displays do this by attaching the display to the viewer’s head; projection-based systems do this by using very large screens that fill one’s field of view. A full CAVE is a 10 x 10 foot room with projections on multiple walls and the floor; due to space and budget restrictions, this gallery installation will only have a single 8 x 10 foot screen; when users stand up close, it will still (more or less) fill their field of view. The screen is rear-projected so that people can stand close without casting shadows on the computer imagery.

The display is stereoscopic, similar to 3D movies. The technology we use is polarized stereoscopy. Two projectors display different images, one for the left eye and one for the right eye. The projectors have different polarizing filters, and viewers wear matching polarized glasses to see the 3D effect.

A six-degree-of-freedom tracking system is used in VR systems to allow the computer to know where things (such as the user’s head & hand) are, allowing direct physical interaction with the virtual world, rather than having interaction mediated by a button/menu/etc GUI. In our case, we won’t be tracking the head (which normally is used to draw the graphics from the tracked person’s viewpoint), since several people will be viewing the display simultaneously, so we will use a fixed viewpoint for the graphics. We will use the trackers to allow 2 or 3 people to fly the kites – the ends of the virtual strings will be attached to the physical trackers, which the people can move around in 3D.

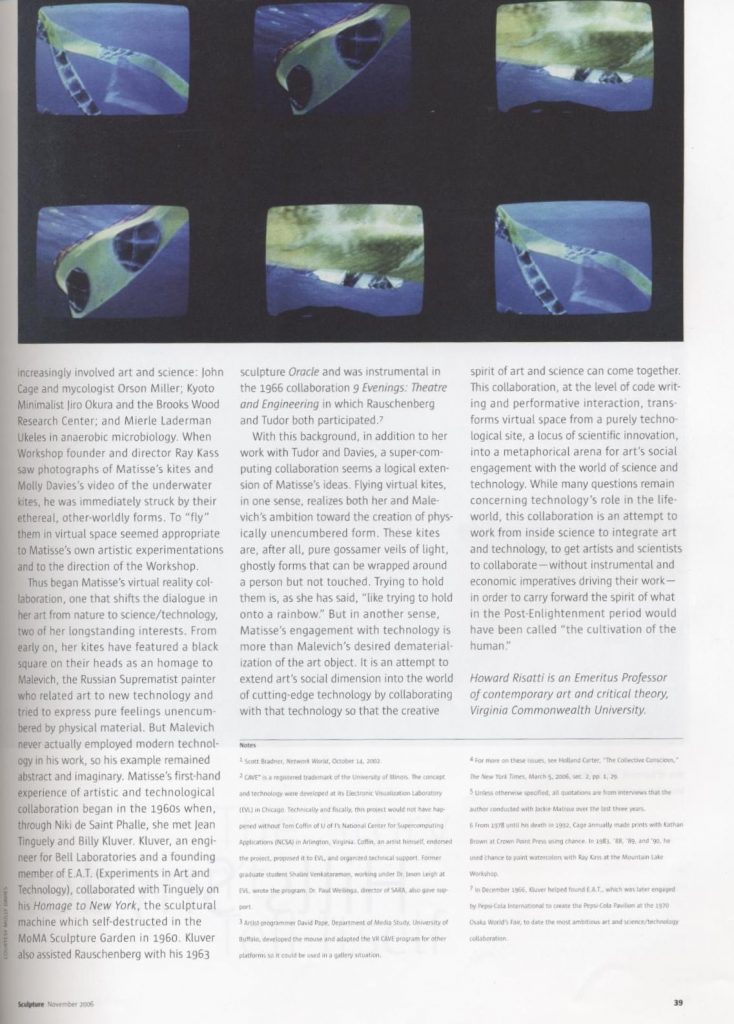

The sound for the piece is music by Tom Johnson. The music is dynamic – it plays in response to the motion of the kites, as manipulated by the viewers. The kites themselves involve a physics simulation known as a “mass-spring model”. Each kite is treated as a mesh of points; the points are affected by physical forces such as wind and gravity, as well as a “spring force” that keeps the kite together as a single surface. The earlier versions of the piece used supercomputers to perform detailed simulations of the kites, with the data being streamed back to the VR system over high-speed networks. As

we don’t have such resources for this installation, a much simplified version of the simulation will be running on the single Linux PC in the gallery. The motion of the simplified kites will still look very similar, just with less detail, and perhaps less realistic (although this is not likely to be apparent to most viewers).

The whole VR Installation consists of 2 or 3 PCs (one with a high-end “gaming quality” graphics card), an electromagnetic tracking system, 2 projectors, polarizing filters and glasses, a special polarizing-preserving screen, and speakers. We assembled the system ourselves at UB from these parts; some companies sell similar systems pre-packaged, but for a lot more money.

Dave Pape

Assistant Professor

Media Study, University at Buffalo

Related

“Airborne Abstraction”, ART IN AMERICA reviews Jackie Matisse’s exhibition

SCULPTURE MAGAZINE review on Jackie Matisse

Categories: projects

Tags: Jackie Matisse