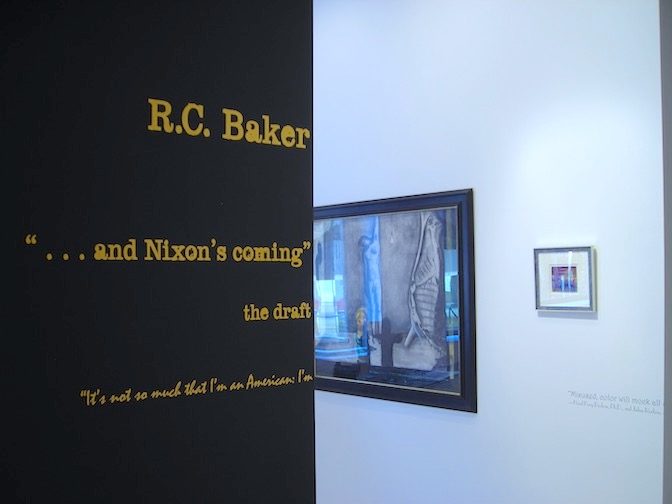

The Brooklyn Rail reviews RC Baker’s solo exhibition, “…and Nixon’s coming” the draft

by Emily Warner

Zone: Contemporary Art, April 2-May 30, 2009

Kirby Holland, the fictional protagonist of R. C. Baker’s ongoing novel-cum-exhibition, explains his art-making process this way: “I put…these collages…together as grounds, the surface you paint on,” before laying the abstract designs on top: “I need some grit, something to hang my compositions on.” That description is a fitting one for Baker’s project as a whole, a collage-like, multimedia narrative that uses the structures of history as the grit for its fictional tale. The edges of the story emerge like pieces in a puzzle: chapter headings line the gallery walls (“Part i: The Fractured Century”), and scribbled notes and studies sketch out forms fully realized in paintings across the room. As a writer, artist, graphic designer, and art critic, R. C. Baker is a polymath, and his current project is a testament to the richness of overlapping artistic modes.

In its present installation, “…and Nixon’s coming” lives in two places, Baker’s in-progress novel draft (available for perusal and purchase at the gallery) and the exhibition. Neither is definitive. In fact, what makes the project so compelling is the detective work the viewer must do to fill in the story’s gaps, linking motifs from work to work, and from text to image. At the center of the narrative is Kirby Holland, to whom all the work in the show (made by Baker over the last few decades) is attributed. Written in the novel in a jaunty third-person, Holland seems more stock figure than fleshed-out character. It’s in his putative drawings, studies, and paintings—intimations of an inner personality and a set of working artistic concerns—that we really catch a believable glimpse of him.

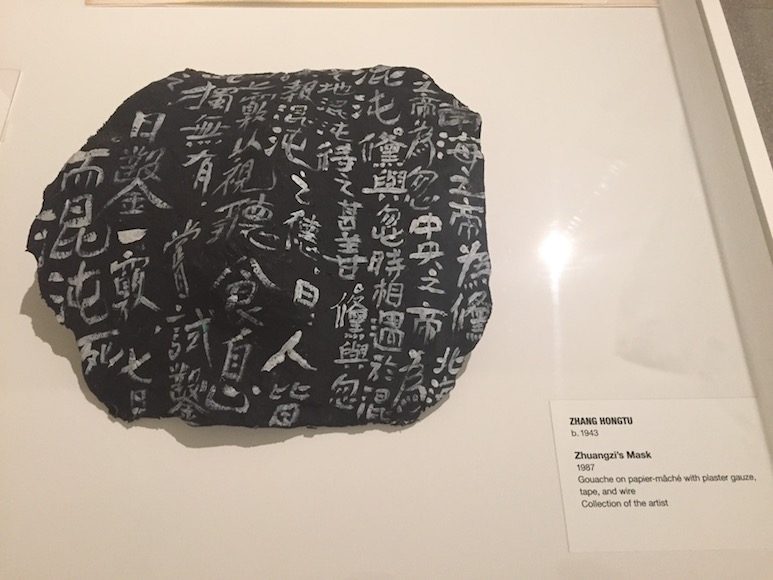

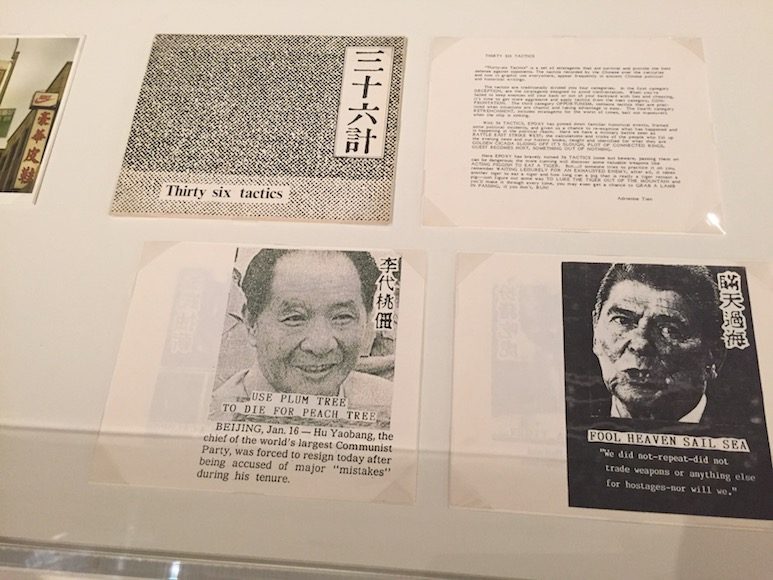

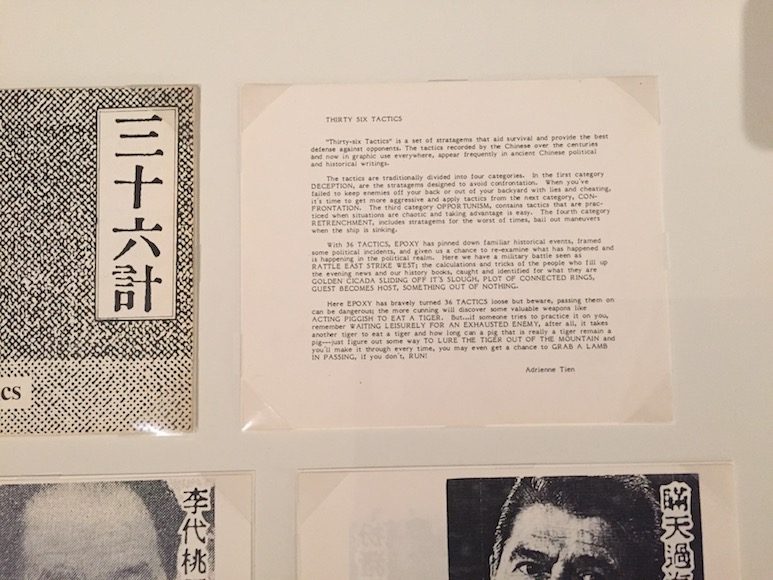

That glimpse plunges us into a cultural and art historical tangle: in Holland’s oeuvre are references to Eakins, Hopper, comic books, Abstract Expressionism, war, and nuclear disaster. These references are constantly edited into new combinations and overlaps. Nothing is ever final in Baker’s project, and a sense of textural, pulpy accumulation—the accretion of drafts, collage layers, galley pages, reworked storyboards—runs throughout. A few pieces are executed directly on printing-press waste; in another series, flung drips of paint are outlined with careful, colored contours, lending high painterly abstraction the printed oomph of a comic book splat. It’s the visual slag of American history, and the manipulations and rewrites to which we subject it, that forms the real subject of the exhibition.

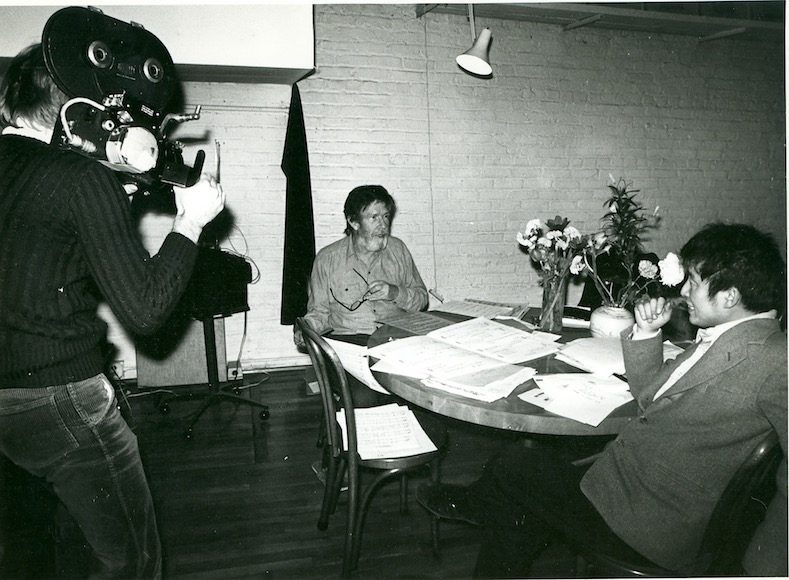

This reworking is not just an aesthetic project; the pithy (if dizzyingly self-referential) “After Krivov, Rockefellers, and Warhol” takes us into more pointedly political terrain. Caked gouache, splotched onto a woolly black xerox of Andy Warhol’s infamous “13 Most Wanted Men,” blots out the face of each mug shot. The work alludes to the whitewashing of the original 1964 Warhol mural by Nelson Rockefeller, and also to the actions of N. A. Krivov , a fictional Soviet filmmaker we meet in the novel as he peruses Stalin-doctored photographs with their unwanted members airbrushed out of the scene. Reproduction and erasure, Baker suggests, are dangerous if creative prospects, and we find them in the paranoid machinations of Soviet Russia as often as in the bourgeois mores of capitalist America.

Of course, the question remains: how effective is Baker’s occasionally bizarre project? For it to work, you need to be curious enough to follow up on its disparate threads. Many viewers may stop here, uninterested in penetrating its rather insular depths. Other authors have used a non-fiction model as the structure for their fictive worlds and characters (John Dos Passos’ USA trilogy and William Boyd’s Nat Tateboth come to mind), and yet Baker’s project stands somehow outside of this vein. His characters lack the practiced interior nuance of properly literary personages and the writing, while always vivid, can be heavy-handed. Indeed, thinking of “…and Nixon’s coming” as a literary project may be the wrong way to go. It’s more a purely visual narrative: the paintings, the sketches, the space of the show act as vignettes, imagistic moments taken from a shifting storyline.

The rewriting we see in the visual works is directed in toward the author, too: Baker has sampled from pieces completed long ago in other contexts, assigning them new authorship and meanings. Krivov, lying in the snow at the feet of Soviet interrogators, performs his own kind of interior rewrite, a cinematic fade-out of the scene around him: “Ah, look how the sun turns that scrub tree into black tendrils…You could fade into a witch’s claw or the Devil’s hand from that,” he thinks. “But that’s stupid and obvious.” There are moments in Baker’s project that feel obvious, too. But it’s nevertheless a vivid evocation of postwar America, and a compelling meditation on the politics of reproduction and appropriation. Eminently fluid and rewritable, Baker’s draft implies that making art is always a form of manipulation, and at times a dangerous one. His project speaks eloquently to the attempt to forge something real—to pick out a storyline—from the mess that is lived experience.

Source: https://brooklynrail.org/2009/06/artseen/rc-baker-and-nixons-coming-8260-the-draft

Related:

The Brooklyn Rail reviews RC Baker’s solo exhibition, “…and Nixon’s coming” the draft